Ten years ago, after I got back from Burning Man 2013, I had a eureka moment and realized how I could make my kids’ book really work. This was just after I was squeezed out of my last corporate job, doing game design at Amazon. At this point, I had been working on Grandmother Fish for almost 15 years, and in fact I had stalled on it. With Grandmother Fish on hold, my then-current project was a book about the historical Jesus and the ways that we are living in a world that he made.

As it happened, I was soaking in my hot tub in a highly relaxed state, thinking about the earliest sorts of language. I had been reading The Symbolic Species by Terence Deacon, which lays out how language might have developed (unconvincingly, I might say). It occurred to me that in primeval times a wise elder might have mimcked the actions of an animal in order to convey information about it, and then it hit me that in Grandmother Fish the kids should mimic the “grandmothers.” I shook all over, and I knew that I had the secret of getting the book to work, only better than I’d originally imagined.

Up until this point, the book had called the child’s attention to anatomy, such as “Great-Great-Great-Grandma Fish had bones.” With the switch from nouns to verbs, “bones” got changed into “wiggling” and “chomping.” Verbs are better than nouns: they’re more fun, they engage preverbal kids better, and they’re more memorable. A mother of two autistic kids tells me that Grandmother Fish a great book for them.

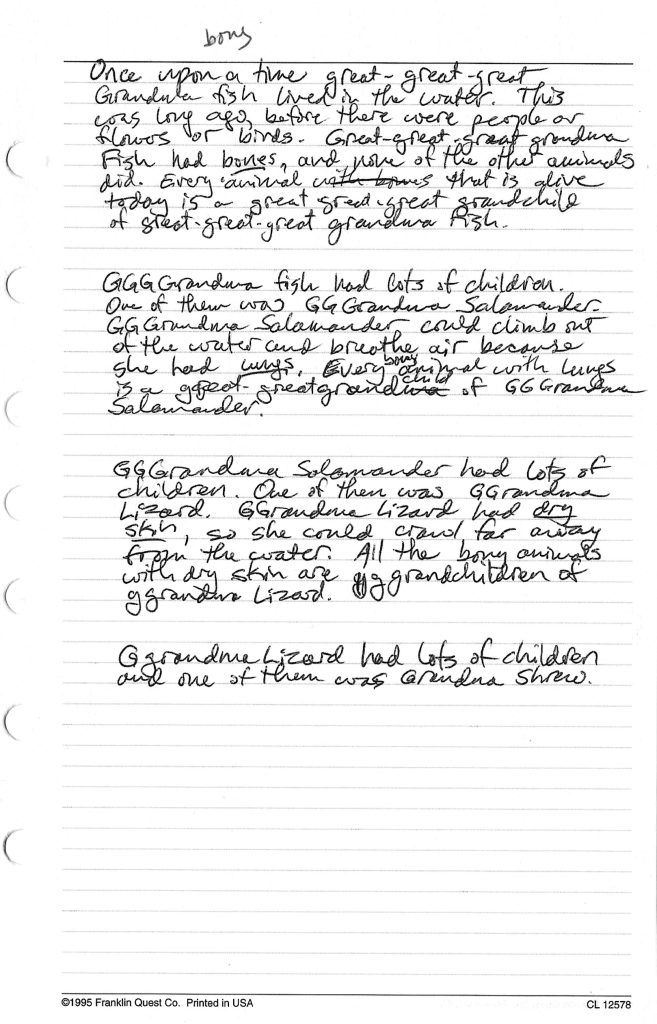

Here are some early notes that I wrote as I struggled to frame the big ideas in Grandmother Fish.