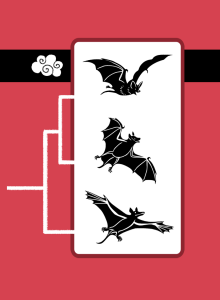

The prehistoric mammals of the air are bats, two early bats, Icaronycteris and Onychonycteris, and an even earlier protobat, which is hypothetical. Icaronycteris (“Icarus bat”) evidently hunted moths with echolocation about 50 Mya, which bats commonly do today. Onychonycteris (“clawed bat”) is the most primitive bat found so far. It had claws on all five of its wing fingers, unlike two for Icaronycteris and one for modern bats. These flying bats evolved from hypothetical protobats that could glide. They may have evolved from tree-climbing mammals that hung upside down to eat fruit or worms in the fruit. Today we think of bats as living in caves, but originally they evolved in trees, as did the first placental mammals.

May 8, 2017

by Jonathan Tweet

Comments Off on Chiroptera: Gliding, Flying, and Echolocating